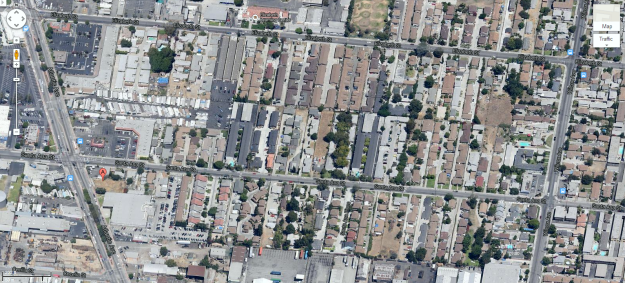

Our inaugural look at development patterns in Glendale starts with W Wilson Ave, which runs from Brand Blvd, Glendale’s main street, to San Fernando Rd, which forms the border with Los Angeles and has a decidedly more industrial aesthetic.

For readers outside SoCal, Brand Blvd is Glendale’s main commercial street, home to everything from Glendale’s small skyscraper district to car dealerships to Rick Caruso’s wildly successful Americana at Brand, along with a wide variety of local businesses. Glendale’s early planners put a stunning view of the Verdugo Mountains to the north, and later planners in Los Angeles anchored the view to the south with the Library Tower. Brand serves as the west-east dividing line in the city, and it’s here we’ll start our journey down W Wilson Ave – down indeed, as this entire part of Glendale slopes gently west towards the LA River.

Downtown Glendale

Well, we’ll almost start at Brand. I’m going to cheat, and start one block east at Maryland, in order to offer up a couple more buildings. First up is the Maryland Hotel, one of only a few pre-war (World War 2, that is) multifamily buildings we’ll see. How do we know it’s pre-war? Fire escapes and no parking!

Kitty corner to that is a construction site, future home of the Laemmle Lofts – a mixed-use development of 42 apartments, a restaurant, and a 5-screen movie theater.

Across from that on the south side, there’s a one-story commercial building housing some restaurants and medical offices.

This side of the block has a nice mid-block pedestrian court leading to The Exchange, one of the oldest developments of the “new” downtown.

On the northeast corner of Brand and Wilson, there’s a Jewelry Mart in an older one-story commercial building, fitting since Glendale is the Jewel City.

There’s another set of older one-story buildings across Brand, on the north side of Wilson, with small retail spaces that are the perfect fit for local and niche businesses. Los Angeles in general has a wealth of this type of space; let’s hope the commercial construction market picks up so that rents don’t start to rise too much.

The building at far right is currently vacant; it used to be a Staples but apparently before that it was a Woolworth’s.

On the south side of Wilson, stretching from Brand to Orange, is a big, bold symbol of the new downtown Glendale: The Brand Apartments.

There’s a lot to talk about here, so let’s take a closer look. First off, let me say that I love this building. I think it looks great. Since it’s got frontage on Brand, which is by far Glendale’s highest-demand retail street, the retail filled up almost instantly with a Chipotle and a Tender Greens. They may not be your cup of tea but established brands that can pay higher rents are what you’re gonna get in new retail more often than not. The mix of businesses in the older building across the street is a reminder of the importance of having some old buildings. Of course, let’s not forget that if you don’t have any new buildings today, you won’t have any old buildings tomorrow.

Here’s a shot of The Brand showing its neighbor to the south, the 20-story Glendale City Center office building. I’m told the zoning at The Brand would have allowed for another 20-story building, but the market for high-rise residential just isn’t there.

Here it is looking southeast back towards Brand.

The next block west is the second part of the same development, and again, I think they did a fantastic job.

The horizontal elements break up the façade nicely, the vertical stone-faced element is a beautiful accent, and the orange support is a nod to the first building that ties things together without being repetitive. The orange accents are also a nod to Orange St, which runs between the two buildings, and now has one of the more urban vistas in Glendale.

Note how the second floor is cantilevered out over the sidewalk, with the balconies projecting further. Here’s another shot showing the second building doing that.

A reliable source tells me that the edge of the second floor projection is at the property line. I like the effect; it creates a wider sidewalk at street level, but doesn’t make the street room feel any wider, so it still feels like a downtown.

The north side of the street here is another block of small, older one-story commercial buildings, home to a mix of small restaurants and retail.

A Big 5, super convenient if you’re in need of outdoor supplies, takes us to Central on the south side, with the north side being a parking lot.

The northwest corner of Wilson and Central is another strip mall, while the southwest corner is currently under construction with another mixed-use development.

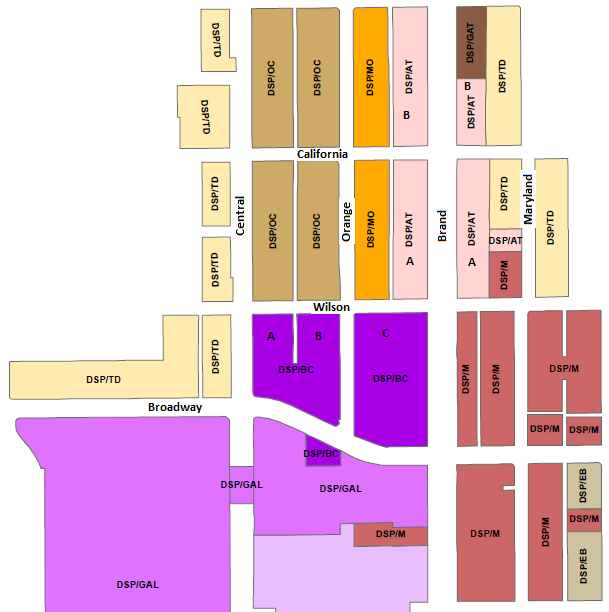

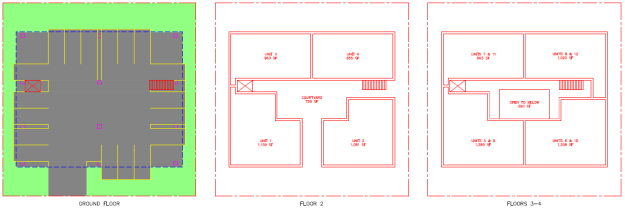

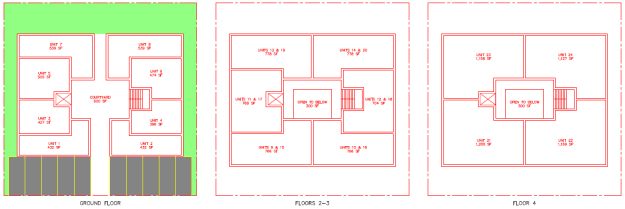

Development in this area is governed by the Glendale Downtown Specific Plan, designed to encourage mixed-use development – the “18-hour city” as official plans call it. The zoning for this area is shown below.

The zoning regulations of interest to readers are summarized below:

Note that the zones with the highest density, DSP/BC-B and DSP/BC-C, are occupied by The Brand apartments and Glendale City Center, but there’s a lot of area with 4-6 stories by right still available. Parking requirements are one spot for singles and 1-bedroom units, two spots for all others, and one guest spot for every 10 units for projects of 10 or more units. This probably sounds like a lot to many readers, though it’s less than required elsewhere.

Vineyard – Central to Columbus

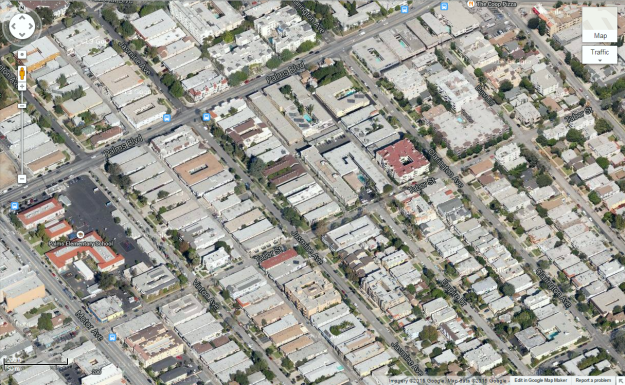

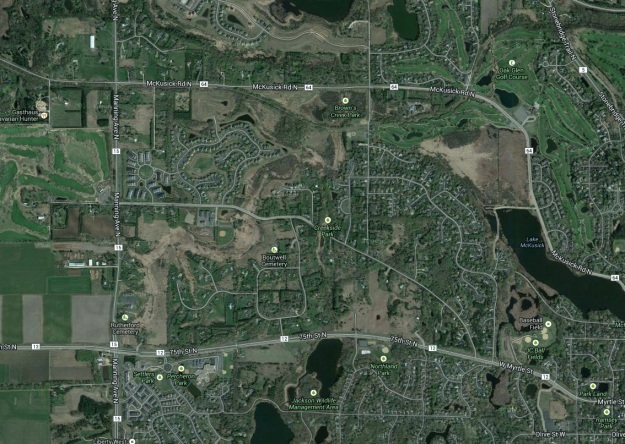

Past here, we’re out of the Downtown Glendale Specific Plan and into West Glendale, or Vineyard if you want to get particular about it, and development changes to smaller scale, all residential buildings. If you haven’t already, you’ll want to open up Google Earth and turn on 3D buildings so you can see what’s really going on; it’s totally impossible to figure it out from the street! Development here offers a lot of inspiration for how to densify existing single-family neighborhoods, but wily West Wilson hides a lot of its tricks from view.

First up, this handsome pre-war apartment block called Canterbury Court. Note its size relative to its neighbor! The Tudor-ish façade is interesting too, since that style enjoyed a renaissance during the 1980s apartment boom, as we’ll see later. The age of many buildings on Wilson is missing in this handy database, but it does have data for Canterbury Court – 1928.

The first building on the south side of the street is this single-family house, with an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) behind it not shown.

West of that is our first trick building. From the street, it looks like a simple fourplex, with numbering (330, 330 ½, 332, 332 ½) that evokes prewar patterns.

Check it out in Google Earth, though, and this fourplex has a hidden ADU building (can we call it a rear house!?) that looks like it has another four units! This unimposing lot appears to be developed at close to dingbat density.

On the north side, we have three larger 1980s apartment blocks (the underground parking is a dead giveaway as to the era of construction).

This one is harder to place (it’s 1975), but I really like the twin chimneys and peaked roof.

Back to the south side, we’ve got a classic dingbat (1961) and a building that I’m guessing is from the 1980s just because it looks like boatloads of unprofitable condos built around Lake Tahoe at the same time (and indeed, it’s 1987).

The next building west puts on the front of a single-family residence (SFR), but it’s got an ADU out back and it’s actually a duplex itself.

Moving back to the north side, we’ve got an SFR and a dingbat, built in 1962.

Well, at least that’s what we have in front! The dingbat’s got a rear house that appears to be two more units, and the SFR has an ADU building.

West of that, there are three buildings that genuinely appear to be SFRs.

Back to the south side again, there’s another classic dingbat, and an older SFR.

We’ve then got another dingbat with a rear house (built 1963) just peeking out into view.

A newer single-lot apartment building (built 2005) and two large dingbat-like buildings (1986 and missing) take us to the corner of Columbus on the south side.

On the north side, three SFRs take us to Columbus. The first has a couple units over a carport in the back, and the second has a single ADU. The houses all date to the 1910s and 1920s.

Vineyard – Columbus to Pacific

This block starts with a bang, with dueling dingbats on the corners, both built in 1963.

After that, on the north, we have an SFR with a four-unit rear house behind it, and a large 1984 building.

On the south side, we have a single SFR (just visible on the left), and an SFR with a multi-unit ADU behind it.

This is one of the trickiest blocks on W Wilson; housing units are everywhere – blink and you’ll miss them. Fortunately we have an alley between Wilson and Broadway to help us get a little better view on the south side. The next two buildings on the south side are what looks like an SFR and, um, what?

Maybe we can get a better view from the back.

Yep, that’s three cottages with a two-unit rear house over a carport. And surprise: totally invisible from Wilson, there are two little buildings behind the SFR

Next up is another larger structure, dating to 1991, the very tail end of the 1980s boom.

This is followed by another SFR with a four-unit rear house.

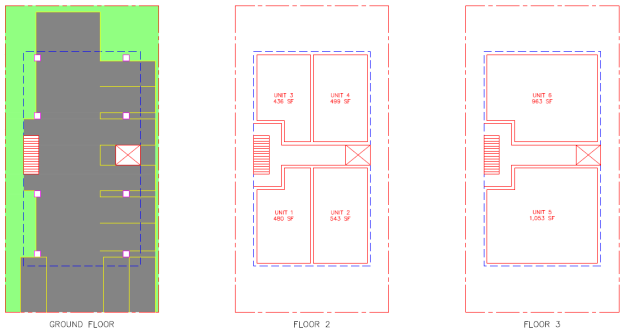

Note that there is a wide variety of shapes and sizes, but the size isn’t necessarily a good proxy for number of units! In fact, the adjacent building to the west is a newer project, taking up 4 lots, but appearing to only have 18 units (4.5 units per lot, the maximum allowed by the current zoning). They’re certainly larger units, but on a dwelling unit basis, this building is less dense.

Back on the north side, we have two SFRs, but they both have ADUs, hidden but for the subtle house number that can be seen at the edge of the yellow house.

There are also two SFRs across the street on the south side, and the one on the right looks to be the only unit on the lot. The one on the left has a second house in the back, hidden from view on Wilson.

There are two more SFRs to the west on the south side, with the left one harboring a four-unit rear house, and the right one harboring a small parking lot for, um, what? The buildings across the alley?

The north side of the street is much more straight-forward: several 1980s apartment buildings and then two SFRs to take us to the corner of Pacific. The apartment building on the right is from 2002.

The south side finishes up with two SFRs that, of course, have ADUs out of sight. They’re actually big enough to be called houses in their own right.

Vineyard – Pacific to Concord

Ok, ready to push through the last block? Well, plus a little coda, and a zoning discussion?

As we’ll see, the further we get from downtown Glendale, the less dense the development gets. The southwest corner of Pacific and Wilson is the last big pre-war multi-family building we’ll see. The architecture, lack of parking, and numbering scheme (500, 500 ½, 502, 502 ½) are the giveaway.

Next, there’s a few SFRs; the one on the left has an ADU in the back. With only a few exceptions, the SFRs on this block date to the early 1920s.

The north side of the block starts out with SFRs as well; I think the center one in the first picture has an ADU but it’s hard to tell from the street. The house in the center of the second picture definitely does, but it’s not easy to see. The one on the right in the last picture also has an ADU, which can be seen in Google Earth.

On the south side, we have the first large apartment building on the block, taking up two lots. This building was built in 1979, before any downzoning, at the head end of the 1980s boom.

Two true SFRs with no ADUs on the south side take us to Kenilworth Ave, a small local street.

Next, on the north side, we have a single SFR, followed by a large 1985 apartment building that takes up four lots and appears to have about 20 units. The landscaping on the street makes it almost impossible to see all four buildings at once.

On the south side, there’s a 1987 building and a 1963 building, both typical for their time.

This is followed by a small SFR set so far back on the lot that one might conclude this was originally an ADU to a dearly departed main dwelling. However, if that’s the case, the original house has been gone since at least 1989, Google’s oldest aerial image for the region. The sign out front announces a proposed triplex on the site, the greatest number of units allowed by the current zoning.

Next to that is a 1980s-looking building that shows how much more density was previously allowed.

Back on the north side, there’s an SFR with an ADU peeking out; in Google Earth, it looks like the rear building actually has two units.

The next house west straight up has a second house in the back yard.

On the south side, there are two handsome SFRs; at left, an ADU can be seen, and there is a third unit totally hidden from view.

Next to that is a large apartment block on two lots – two buildings, not identical but fraternal twins, dating to 1983 and 1985.

Further down, a classic modern stucco apartment house from 1963 (hey, didn’t we see you on dingbats dingbats dingbats?) and a Tudor-ish 1974 building on four lots.

Across from that, on the north side, are several SFRs; all but one have ADUs, but you’ll have to look in Google Earth to see them.

The north side of the block continues to stretch west with SFRs; some have ADUs, while others are actually duplexes, a type we haven’t yet seen much of on Wilson.

You’ll really have to look closely in Google Earth and Street View to try to see what’s what. Here’s a few where you can catch a glimpse of the ADU.

Here’s one of the more obvious duplexes.

Rounding out the residential units on the south side, we have an SFR (with an ADU not shown) and a dingbat with a rear house.

There’s a large one-lot 1973 building and then two true SFRs without ADUs.

The south side then goes industrial, with some single story office/warehouse type buildings.

Vineyard – Concord to San Fernando

The last little block takes us down to San Fernando Rd, which runs next to the Metrolink tracks that form the boundary with Los Angeles. This block is made up of one-story industrial uses.

At the corner of San Fernando, there’s a small local hangout.

Vineyard – Zoning

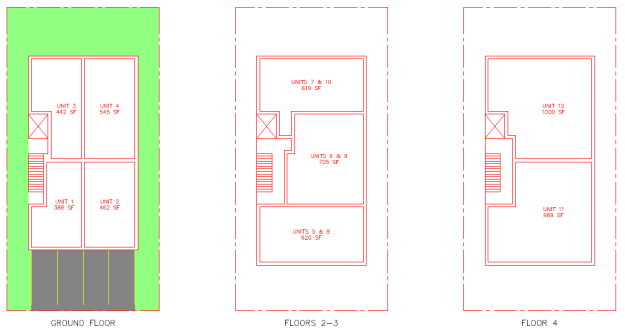

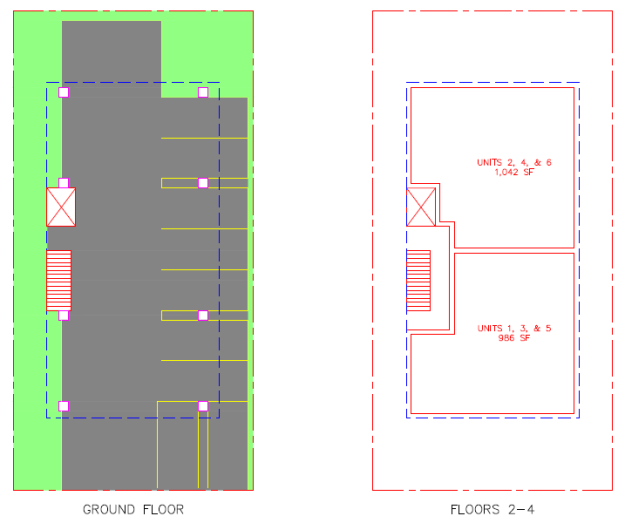

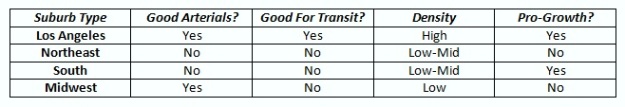

Zoning west of Central is covered by Glendale’s general zoning plan.

From east to west, the blocks of W Wilson are zoned R-1250, R-1650, R-2250, and IMU. The R zones are residential multi-family zones, where the number indicates the required lot area in square feet per unit. IMU is industrial/commercial mixed use. Parking requirements are 2 spots per unit, except 2.5 spots for 3-bedroom units and 3 spots for 4-bedroom units.

Thus, the permitted residential density on W Wilson steps down as you head west towards San Fernando Rd. Lots on the north side of Wilson appear to be about 50’ x 140’ lot, which translates to 5, 4, and 3 units per lot; on the south side, lots appear to be about 50’ x 175’, which translates to 7, 5, and 3 units per lot.

Which Way, W Wilson?

West Wilson Ave presents an interesting variety of residential housing types, from single-family houses to large apartment buildings, backyard cottages to dingbats with rear houses. In these few blocks, it captures both the opportunities and challenges for housing in greater LA in general.

The housing types of W Wilson point the way forward for natural growth of less dense neighborhoods, such as centrally located single-family areas. These options – ADUs, rear houses, small apartment buildings – are some of the best ways to improve housing affordability. They’re lower cost to construct, and don’t result in the loss of a lot of existing units. They allow for an evolution of building types rather than a sudden change. There are still development opportunities on Wilson; you could buy one of the remaining SFRs and built townhouses or put up some ADUs in the back. We would do well to allow other neighborhoods to grow the way Wilson did.

On the other hand, this area was clearly downzoned in the 1980s. There are lots occupied by SFRs where you can only build 3 or 4 units, despite the adjacent lots having 7 to 10 units. If housing prices in LA continue to rise, there will be pressure to redevelop lots that are currently occupied by a SFR and a few ADUs. Under the current zoning, we won’t end up with more housing units, just larger, newer, more expensive units. In some cases, redevelopment might result in a net reduction of units. It shouldn’t be a radical idea that new development be permitted to be at least as dense as its neighbors. Would a few 5-story buildings really make a big difference in how the street feels?

The foot of Wilson Ave, along with San Fernando Rd itself, is worth looking at in more detail, in a future post. For now, development patterns on Wilson Ave stand as proof that we do know how to do mixed-use projects and residential density in the LA region, when we let ourselves do them.