Sometimes I think that a lot of misunderstandings in the discussion on cities relate to inconsistent terminology. It seems to me that we have four different concepts of what a suburb is, so if we’re going to talk about suburbs, we need to be talking about the same kind of suburb. In my personal descending order of preference, they are:

- Los Angeles: typified by surprisingly dense uniform development filled in on a grid of arterial roadways, usually at half-mile or mile spacing. Development spreads uninterrupted until it runs into an insurmountable barrier, e.g. the Pacific Ocean, 10,000-foot tall mountains, or kangaroo rats. This pattern is a legacy partly of the rancho grants, partly of the US public land system. This is what people think of when they think of sprawl, but it’s actually the least sprawly.

- Northeast: typified by somewhat dense historic town centers, surrounded by low density exurban development. Subdivisions have larger lots, and there are often large relatively undeveloped areas. This is a legacy of development following the pattern of small farms. Virtually all of the characteristics that urbanists like predate the auto age.

- South: as I noted in my post on Boston and Atlanta, this is basically the same pattern as Northeast Corridor suburban growth but without the underlying pattern of historic cities and town centers. The South is what the Northeast would look like if no one had been living there to start with in 1945.

- Midwest: like the Northeast, but even more spread out. Subdivisions are built around small, historic agricultural crossroads, and there can be miles of farmland between exurban towns. Midwest sprawl is typified by an urban footprint that keeps growing quickly, despite relatively stagnant populations, as people decamp the old cities.

In the following sections, I’m going to describe each type in more detail, including why I like or dislike the pattern.

Los Angeles

For LA, let’s revisit the patch of development in Lancaster that I used as a counterexample to Boston and Atlanta.

As I said, this is what most people think of when they think of sprawl. Aerial shots of suburban tracts like this are stock images in any urbanist post about how suburbia is a monotonous, soul-crushing, doomed landscape.

But on many of the things that urbanists claim to care about, Lancaster does pretty well. It has a solid grid of arterials on half-mile spacing, and many of the arterials already have bike lanes. You could throw down bus lanes with POP fare collection and stops every half mile that would basically be Jarrett Walker’s dream grid (well, without anchoring). Add some mid-block crossings for pedestrians and boom, you’re good.

Now, depending on the whims of developers and local planners, there can be a lot of cul-de-sacs and indirect streets. You might have a circuitous path to get to one of those arterials – at least if you’re in a car. I’m always a little amused at the hand-wringing over street grids. Y’all were never kids with bikes? I grew up in a place with lots of cul-de-sacs and disconnected streets. We knew where we could cut through. That’s not to say we shouldn’t try to make new developments better by bringing back the jog, but this is a much easier problem to solve than those faced by other types of suburban development.

Then there’s that sneaky LA density. Let’s take the block in the image above bounded by J, J-8, 15th East, and 20th East. By my count, there are 483 SFRs and somewhere in the vicinity of 190 apartments (making some conservative assumptions), along with, very roughly, 125k SF of retail. If we assume 3 people per house (in line with Lancaster demographics) and conservatively say 1.3 people per apartment, we’ve got about 1,700 people living in a quarter of a square mile (sq mi), for a density of 6,800/sq mi.

In other words, this patch of the Antelope Valley – mostly SFRs, with a big-ass parking lot in front of the retail, the kind of place that people like James Howard Kunstler would call crudscape – already has a density higher than the weighted density of the Washington DC area, and it’s not far behind places like Philadelphia and Boston. Even if we base the calculation on the least dense sixteenth-square-mile, which has 154 SFRs, the density is 5,500/sq mi. Weighted density of Portland, for reference, is 4,373/sq mi. Oh, and it’s not even built out yet.

That last point is another secret strength of the LA suburban pattern: no one is under any delusions about what we’re doing here. Everyone expects and hopes that those vacant lots will get developed. The home builders want it. Retail and business owners want it. R Rex Parris wants it. And the folks in the apartments on the other side of J-8 aren’t going to mourn the loss of those dusty lots. If you were to liberalize the zoning, eventually you’d end up with dingbats like Palms or skinny-but-deep redeveloped Cudahy lots like you see in their namesake city and places like El Monte. This year, Lancaster changed its zoning to allow accessory dwelling units. In LA, the expectation is that more people are going to show up, and that’s a good thing – the opposite of the premise under which suburbs in New England operate.

Northeast

Now, in total contrast to LA suburbs, where people basically expect and want growth, the assumption in New England is that you have a town perfected by the descendants of Myles Standish and John Winthrop when they settled it in 16-whenever, and all this growth is irredeemably ruining the historic character of the town. Let’s have a look at The Pinehills, a recent major subdivision in Plymouth, MA.

The Pinehills is what passes for smart growth in a lot of the Northeast; the Boston Globe says the state uses it as model, in an article that proves my point by citing a resident as a 10th-generation descendant of William Bradford. The permits allow for a little less than 3,000 houses on 3,174 acres – or in other words, a final density of about 1,800/sq mi, well down into exurban territory and on par with places like Bismarck and Pocatello. New England is the land of two-acre zoning. The expectation is that the intervening area will never be developed. Every suburban resident in Massachusetts subconsciously fancies himself an English baron, entitled to undeveloped wood lots for fox hunting or whatever.

This is a development 45 miles out from Boston. The low density means that it is always going to be impractical to serve the area with transit. The insistence on rural character means that the arterials are unpleasant and unsafe for biking and walking. As I said in my Boston/Atlanta post, every dense neighborhood that exists in New England existed 60 years ago. Tom Menino and Joey C can conjure a few new urban districts out of semi-vacant industrial land, but that’s about it.

It’s important to note that this a fundamentally different mindset, and it affects all aspects of policy. For example, recent MBTA commuter rail extensions like Newburyport serve towns with comically low populations and population densities (Rowley, population 5,856, density 290/sq mi) that have no realistic prospects for appreciable growth. Deval Patrick gets accolades from Streetsblog for proposing “smart growth” density of 4 SFRs or 8 apartments per acre near transit stations, which will produce population densities on par with. . . Lancaster. Of course, that’s only if they actually develop an entire square mile around the station. Which they won’t, because it’s New England.

Despite all of this, the Northeast still benefits from legacy town and city centers. I’m not sure what you can do with the low-density exurbs, but the presence of these nodes at least means that people see what density looks like.

South

With the South and Midwest, we’re into territory I don’t have personal familiarity with, so I welcome any thoughts or corrections. In general, it’s harder to find “typical” suburban development outside of California, because there’s more variability. For the South, I’m going to revisit the Atlanta area: Redan, which is just outside the 285 beltway on the east side of the city. I tried to find an area of development that had some apartments, since they seem to be more common in the South than in the Northeast or Midwest. I’m looking at the area between the 278, Wellborn, Marbut, and Panola.

This part of Redan has a density of about 4,900 sq/mi, which would make it very dense by Atlanta standards, where weighted density is only 2,173 sq/mi. Part of the problem is that it’s just very hard to pick a representative plot here. The area sprawls so far that the edges are mostly undeveloped, which makes them unsuitable for measuring the pattern in the region. Here’s another shot, west of the 285, in Powder Springs. Looking at the area between Powder Springs, New MacLand, Macedonia, and Hopkins.

This area has a density of about 2,600 sq/mile, which is in line with what we expect for the region.

Looking around the South in general, using old images available in Google Earth, it does seem to me that more recent development has been build a little more densely – perhaps as developers have realized they’re running out of land? It also seems that the planning and development culture of the South is such that the region wants to keep growing in population, which is not really the case for the Northeast and Midwest. However, I’m not sure if the political and social structure of the South is ready for upzoning and density on the level of Houston or Los Angeles. The low density of the South makes it difficult to provide effective transit and more costly per capita to maintain infrastructure.

The other thing that will challenge the ability to provide effective suburban transit in the South is, like the Northeast, the mishmash incoherent network of arterials. Unlike Los Angeles and the Midwest, the South and the Northeast inherited a winding network of colonial roads that make it very hard to design transit routes that don’t have a lot of turns. Whereas Western runs over 25 miles due south from Los Feliz to San Pedro, in the South and Northeast, you’re lucky to find an arterial road that doesn’t change direction at random and dead end after a few miles. In addition, the insistence on maintaining “rural character” means that there’s often public resistance to widening arterials (even to provide transit) and building things like bike lanes and sidewalks.

Midwest

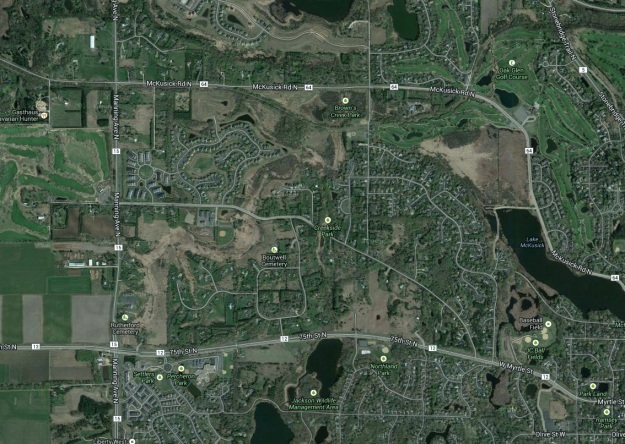

From a 10,000-foot view, the Midwest seems to have more freeways than the rest of the country, along with bigger suburban lots. That, combined with low population growth, seems to me to make this the purest form of sprawl, and the least sustainable. For our example of Midwest suburbs, I offer up Michele Bachmann’s district: Stillwater, MN. Take the area between 75th St, Neal, McKusick, and Manning.

This area checks in at a density of about 1,200/sq mi, with 300 SFRs and 150 apartments. The weighted density of the Minneapolis MSA is 3,383 sq/mi, so this area is low and it may yet get denser. However, it’s hard to see it reaching Lancaster densities anytime soon. On the plus side, the Midwest does have a good arterial grid.

Notice that many of the subdivisions in the Midwest have large lots – what Californian planning would call “estate residential”, and relegate to a few affluent communities like Acton and mountainsides that are too steep for denser development. You won’t find any development like that in the LA Basin, the Valley, or the vast majority of Orange County. Where it still exists in the IE – for example, Fontana – the lots are being further subdivided into typical LA suburbia.

In the Midwest, though, like the Northeast, there’s no expectation that these areas will ever get any denser. With low population density, a mindset that opposes further development, and far-flung subdivisions, it’s hard to see how these areas could be served well by transit, or become very walkable. When I listen to Charles Marohn, I sometimes have to remind myself that he’s talking about places like Baxter, which, other than being called a “suburb”, has remarkably little in common with a place like Corona.

Summary

I promise you, all of the images in this post are at the same scale. It is interesting to look at them next to each other and compare. The differences that I’ve outlined in this post explain why I think the LA development pattern is the best and why I’m essentially bullish on the future sustainability of LA.

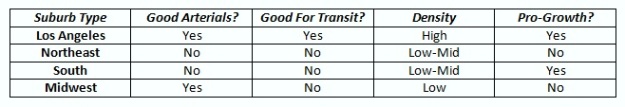

For reference, here’s a quick tabular summary of the differences between these four types of suburbs. Suitability for walking and biking pretty much correlates with density, because if the place isn’t dense enough, you won’t be able to walk or bike to anything worthwhile, even if the infrastructure for it exists.

I would find that many new subdivisions in the Midwest are denser than what you portray; for instance, outside of Omaha ( http://goo.gl/maps/7MHxh ), or Madison ( http://goo.gl/maps/QixE6 ). While Omaha drops the ball on building even marginally useful sidewalks, Madison constructed a sidewalk network more akin to Los Angeles than the Northeast.

Perhaps I am biased as a resident of the region, but I would consider there to be a fifth category as well, Mountain West. Exemplified by Aurora ( http://goo.gl/maps/Uk5Vl ), this typology is categorized by comparatively compact SF residential lots (about 45-70′ by 80-120′, with 60′ by 100′ being the most typical,) and a general tendency to “leave no parcel untouched” development-wise. Main arterial intersections (usually 4 to 6 lanes wide, potentially including bike lanes) usually are surrounded by stick-built three-story apartment buildings next to or across the arterial from smaller strip malls anchored by a full-size grocery store. For walkability, I would generalize this type of development to be about a “C”; sidewalks are provided and of usable width, road crossings, while long, are usually properly timed, and while the pedestrian realm isn’t extremely enticing, you don’t feel like you will be ran over any second. Mountain West can be considered to be either a less intensive Los Angeles or a more intensive Midwest, depending on how it is viewed.

This typology isn’t limited to just Colorado. Here are examples from Billings ( http://goo.gl/maps/Gjfmh ), and Boise ( http://goo.gl/maps/XB387 ).

Thanks for your comments and insights. I was thinking more of upper Midwest (Minneapolis, Detroit, Chicago, etc.) but Madison would certainly fit the bill there. If I have time, maybe I’ll do an update and try to pick some representative tracts in a few of the cities you provided. Omaha and the Mountain West make sense as a watered-down version of California types…

Sort of unfair to the Northeast, because there’s a tendency to “Skyscraperize” the downtowns in the Northeast. It may be hard to create new dense districts, but the old districts are permitted, in recent years, to get denser and denser. Not ideal, but looks a bit different from your description.

There’s a tendency to build skyscrapers in Manhattan, and a select few neighborhoods elsewhere. In Boston, for example, you can build mid-rises and high-rises in the Financial District & Downtown Crossing, but other than that, just on vacant industrial land (North Point, Kendall Square, South Boston Waterfront, etc.). No one is going to skyscraperize the North End, Back Bay, Allston/Brighton, Jamaica Plain, etc. And note that gentrification has resulted in places like the North End getting less dense. I’m happy to see new buildings go up in the cities in the Northeast, but I wonder how much the trend can grow.

I should be clear that the intent of my post was really to look at and compare different types of suburban development happening at the edges of cities. There’s definitely another whole range of development patterns that exist in older built-up areas, and some of them are of course much better by urbanist standards.

Pingback: LA Land Use Patterns Help Reduce VMT | Let's Go LA

Pingback: Types Of Houses » Blog Archive » What Does Detached Home Mean Hd

Pingback: How to Write Your Very Own Pro-Sprawl Trend Piece | Let's Go LA

Pingback: Suburban Geography and Transit Modes | Pedestrian Observations

Pingback: Housing options at the census-defined urban area level | zero mean error

I think Florida might be a different form still from the rest of the south. Due to geographical constraints (everglades, ocean), South Florida is as little as 4 miles wide and up to 100 miles long- but many people travel primarily east-west.

For the other parts of florida, you have the east coast, where there are Flagler’s historical railroad towns along what’s now US-1/Dixie highway generated walkable and largely still intact downtowns, as well as the islands on the other side of the intercoastal waterway, whose inhabitants rarely go to the mainland and where virtually any activity could be completed on foot (though is often performed via a short drive instead). Streets follow a grid, and the need for evacuation routes means wide and regular arterials, which should (in non-hurricane situations) be reserved for protected cycle lanes (wide enough for vehicle use) and bus lanes. On-street parking and parkettes are also good ideas, but those need to be able to be rapidly moved- metered parking and flip-up parkette setups may accomplish this.

This is the case pretty much from St. Augustine south until Homestead along the east coast Jaksonville is its own mess- and closer to a typical southern town- it’s not centered around the beach and the combination of city/county along with the presence of the I-275 beltway meant that nobody was really looking for any kind of concentration of density- but there’s a decent streetgrid, regular arterials, and lot sizes are generally pretty small (though not as small as the intercoastal islands’ beachside plots)

Orlando looks like the rest of the south- lots of cul-de-sacing, not a lot of geographical constraints to concentrate density or development- it’ll grow until it gets shoulder to shoulder with the older beach-side towns and their edge city developments.

St. Petersburg and some of Tampa have the same kind of setup of grid streets, evacuation routes, and small lots as the east coast, but the Tampa Bay area quickly becomes some serious next-level cul-de-sac hell. Even so, the evacuation routes mean arterials are wide and regular.

Naples and Cape Coral follow this pattern- toward the coast and older part of the city, it looks like Florida’s east coast, the farther you go from the water, the more it looks like Greater Orlando’s post-disney subdivision developments.

Florida, Having gone from fewer people than the Bronx to more people than NY state in less time than many of its residents (retirees) have been alive, is pretty pro-growth. But some of the master-planned and cul-de-sacy subdivisions try to ossify against any addition of density or services. The beach-side towns with regular gird streets and short, quasi-walkable distances, are very easy to serve by transit or bike, and adding density in the form of ADUs, duplexes, and small apartment buildings, as well as the high-rise beachside condos, has been going on for a long time.

I’d say much of florida has a chance to look a lot like the denser parts of L.A.- particularly anywhere founded by Henry Flagler. There’s also the ultimate sign of a short-drive community- a lot of places in Florida have dedicated roads or share the road laws in place for golf carts!

Pingback: Four North American Land Systems | Let's Go LA

Pingback: Connect | PlaNYourCity

I like the concept that Western gridded suburbs are more malleable and adaptable than the twisty cul-de-sacs of random hopscotch rural development in the East and South. The two acre zoning of eco-conscious and/or anti-density folks preserves open space, but at the cost of a suburban pattern that can never effectively congeal into anything like a traditional New England town. The catch, of course, is that the folks in places like Lancaster need to want their mile square chunks of sprawl to thicken into walkable transit served mini Main Street nodes. In my experience… they fight it tooth and nail even when a highly successful experiment like the BLVD is up and running. http://www.theblvdlancaster.com/index.php

Mayor Rex Parris proposed shutting down the Metrolink rail station because it was attracting the “wrong element” from downtown LA. No one moves to the Antelope Valley because they long for density and transit. They move there out of desperation when they can’t afford a fully detached single family home with a lawn anywhere else in LA County.

This lack of want is an issue in many places. Hopefully it will change with time and as people see it is not something to be scared of. Parris is another issue altogether; he is really in outer spcae w/ his theories on Metrolink, Section 8, etc.

As for why people move to the Antelope Valley… I’d really like to see this studied in more detail. The 1980s boom had a lot to do w/ local employment in defense industry. The 2000s definitely felt like “drive till you qualify”. Interestingly though, there is very little single-family development in the AV post-bust; it seems that even pretty high prices in Santa Clarita can’t induce many people to move out there at the moment…