In previous posts, I laid out some reasons for focusing some attention on the area between 2nd St and Union Station, and presented an option for improving the 101 in a way that would help restore the urban fabric between downtown and Chinatown. I was originally going to do two more posts, one on land use and one on parks, but they’re so connected that it makes sense to address them at the same time.

Concerning land use, by far the biggest problem in this area is the monolithic area of government buildings, and the accompanying parking uses. In the image below, based on the city’s excellent ZIMAS service, land zoned for public facilities (PF, i.e. government buildings, freeways, schools, fire stations, and so on) is colored blue-green. Other uses per the generalized zoning legend.

The heavy concentration of a particular type of employment, while it creates agglomeration effects, results in inefficient use of infrastructure and land. Infrastructure use is heavy during peak travel periods, and businesses are crowded during workweek lunch times, but the area is practically a ghost town at other times – try hanging out on Temple on a Saturday night, for example. In fact, the blue-green area pretty much corresponds to the district in question.

This is an important thing to keep in mind when it comes to the parks in this area, because the biggest determinant of a park’s success or failure is everything around it. The parks are shown in dark green in the ZIMAS image above.

Grand Park

As one can see, Grand Park is entirely surrounded by government buildings. Some hope that it will become “LA’s Central Park”. Personally, I think trying to make something “our city’s [insert landmark from another city]” is a bad idea, because it sets us up to try to imitate the features of another city and ignore local context. If Grand Park becomes truly grand, there will be no need to promote it by invoking the image of another city. To their credit, the people running the park have done well at programming events and drawing interest in the park.

Their job would be much easier if the land uses surrounding the park contributed a steady stream of passers-by, people for whom the park was a pleasant way between destinations, not a destination unto itself. This is pretty much straight out of Jane Jacobs writing about Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia – and wouldn’t you know it, Rittenhouse Square’s 8 acres are not a bad comparison for Grand Park’s 12 acres, much better than Central Park’s 840 acre sprawl.

This means that over time, we need to encourage a greater mix of land uses around the park. There are three blocks between 2nd and 1st, from Grand to Broadway that are currently pretty empty. One is a vacant lot that is slated to become a new courthouse, one is a mishmash of parking lots, and one is a steel-frame parking garage that looks like it had no business surviving both Sylmar and Northridge. The first is zoned PF, the other two commercial. After Regional Connector is complete, there will be subway stops at 2nd/Hope and 2nd/Broadway, in addition to the existing Civic Center stop at 1st/Hill.

This is going to create market pressure to redevelop the lots. The parking lots should be upzoned to allow residential, commercial, and retail, with no parking minimums. LA Curbed reports that the GSA is hoping to find a developer to build a new office building next to the new courthouse. Realistically, the downtown office market is already flooded with vacant space. Why not allow residential, for which there is a big demand downtown, to be built here as well? This, along with other proposed developments in the area, will help pull the downtown building boom towards Grand Park.

The government buildings surrounding Grand Park should not be doomed for no reason other than trying to satisfy these urban design goals. Over time, agencies will likely decide to build new, modern facilities and at that time the parcels will become available for reuse or redevelopment. For example, when the new courthouse at 1st/Broadway is complete, the existing courthouse on Temple between Spring and Broadway can be redeveloped. Conveniently, LA Downtown News has a good look at this issue today.

Graffiti Pit

There’s currently one vacant parcel fronting Grand Park – the shattered remains of a state government building that was terminally wounded by the Sylmar earthquake, colloquially known as the graffiti pit. For reasons I cannot comprehend, the powers that be have decided that solution for this lot is More Open Space – this, despite the fact that the lot already borders Grand Park and City Hall Park. The last thing we need here is more green space.

Before you jump on me, I would implore you to think about how parks work. If that’s not enough, reread the parks chapter of Jane Jacobs. In every article I’ve linked to above, parks are “venerated in an amazingly uncritical fashion”, as she put it. Practically no attention is paid to the land uses around the park that will actually determine if the park succeeds.

A parcel that is bordered by two parks, LA City Hall, the LA County Law Library, and the LA Times should not be a park. It would seem to be a strange use of limited public funds to build yet more open space here. Instead, why not demo the graffiti pit and mitigate any environmental hazards, and then auction off the lot (or lots) to the highest bidders, as I suggested in my post on the 101 in the area? Given current market conditions, residential is probably the most viable use, though this lot is a little bit further from the active areas of downtown and Little Tokyo, which would reduce the desirability.

Unfortunately, we may too far down the open space path to change plans now. Because the virtue of open space is accepted as self-evident, people tend to look askance when you say that a park is a bad idea, and once the park is built, it is very difficult to go back. Nevertheless, I’m still going to try. We really don’t need another park here.

Park 101

To the north of Grand Park, Temple is lined with government buildings on both sides, along with the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. To the west of Figueroa, GH Palmer is building one of its Italian-series buildings, the Da Vinci. North of Temple is the 101 freeway trench, about which I’ve previously written in the context of rationalizing the ramps and improving the street grid. Now let’s look at the Park 101 proposal, which in addition to reconfiguring the ramps would build a deck over the freeway trench with new parks.

Obviously, I prefer my ramp configuration. I’m not sure exactly what Park 101 is proposing, since the “Alternative A” shown in the phasing video looks different than the “Preferred Concept” in the study. But any concept is going to require further study anyway, and the most important thing is to get the ball rolling on a rationalization of the ramps that includes getting rid of the loop ramps that chew up an entire city block. That sets the stage for some selling some property that can help pay for improvements. Park 101 overplans the type of development for my liking; as I’ve said before, we should let the market decide the best use.

Principles for Freeway Cap Parks

To my surprise, the Park 101 Study makes only passing reference to Boston, in the context of increasing property values from the Big Dig. I lived in Boston during the opening of the parks that replaced the 93 freeway elevated structure after the Big Dig tunnels were complete, and there are many lessons to learn about linear parks above freeways from that project:

- The park has to end somewhere, and that location is likely to be unpleasant because it is going to be subject to freeway noise and fumes. No one really wants to hang out at Portal Park. This suggests that the ends of the park should terminate at a building, not a freeway portal. Clearly, in the case of Portal Park, there’s an extenuating circumstance – the desire to provide a view of the bridge – but that’s not the case with the 101.

- Don’t overplan the land uses. It is now almost ten years since the 93 freeway elevated structure was demolished, and precisely one of the designated parcels has been developed – a mixed use block between Causeway and North Washington. On all the remaining parcels, viable development plans have been repeatedly rejected, while the preferred plans have proven untenable.

- Don’t hold the park corridor sacred. In Boston, fanatical NIMBYism has resulted in demands that new development not even cast shadows on the park, which makes it practically impossible to capitalize on the increased land values on the corridor.

- The development is just as important as the open space. The parts of the Central Artery corridor that work well – the North End Parks, the fountain by the aquarium – have strong generators of interest on both sides. The weaker parts – from High St to Congress St – have weak generators on the east side (because there is only one block to a wide expanse of water) and single-use generators on the west side (offices). When the Big Dig started in the 80s, the environmental reviewers arbitrarily decided that 75% of the corridor should be parks because, well, because MOAR OPEN SPACE. Other architects and planners submitted proposals that the corridor should become more like a series of Copley Squares, bounded by development on all sides. In retrospect, these proposals would have made the parks better.

Now, there’s actually another facility in Boston that’s just as instructive: the Massachusetts Turnpike between South Station and Kenmore Square. Like the 101, the Mass Pike is trenched just below street level along this corridor, and the city would like to cap the freeway with development and parks. Unfortunately, since the construction of Copley Place in 1983, no progress has been made. The Fenway Center might start construction next year, but don’t hold your breath – the Columbus Center actually started construction in 2008, but then withered. A proposed overbuild at South Station seems moribund as well.

The take away here is that air rights have negative value relative to regular vacant lots, due to the need for unusual structural designs and restricted work hours. If there are benefits to the city at large, this may be a rare case where I would make an exception about giving subsidies to developers.

We should also realize that for cap parks design is restricted by structure depth. This restricts the types of landscaping and park features that can be installed. Also, since you’re on a bridge, at some point you’ll probably have to rip everything out to rebuild the structure.

Finally, if you cap a freeway over a long enough distance, it’s functionally a tunnel, which means you need to provide expensive things like tunnel ventilation (far more costly for freeways than for transit), emergency egress points, fire standpipes, and so on. Therefore, to be cost effective, we should keep the freeway cap sections short enough that they don’t trigger tunnel reviews.

Note that as is often the case with urban design goals, sometimes there is synergy between goals, and sometimes goals are in competition. There are trade-offs to be made. For example, the desire to terminate the park with a building is in conflict with the fact that air rights have negative value. The desire to connect the city to the greatest extent possible is in conflict with trying to keep the cap sections short. These trade-offs can be a question of how much money we want to spend. It’s easy to say we should have more freeway caps, but recognize that public funds are not unlimited. Every dollar we spend here is a dollar we can’t spend on improvements somewhere else.

Alameda to Broadway

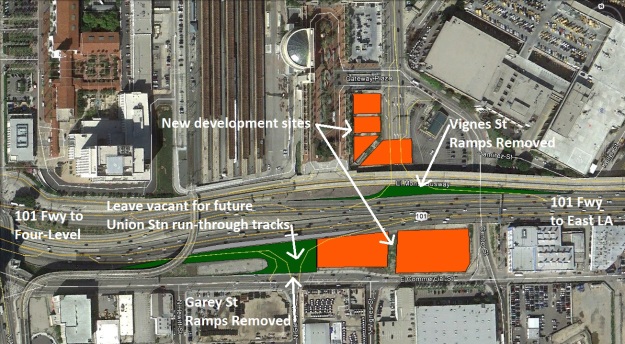

The need for a better connection between Union Station and downtown is the most acute between Alameda and Broadway, and it’s no coincidence that in this stretch Park 101 makes the most sense. Logically, this is also proposed to be the first phase of the project.

With the principles outlined above in mind, I think we can get the benefits of Park 101 without capping as much of the freeway or spending as much money. I agree with the Park 101 study that the logical first piece of the cap is the block between Los Angeles and Main. That suggests that the blocks to the north and south should be covered with air rights developments. In the interest of reducing tunnel ventilation and egress costs, I would consider the leaving the center portion of the block open to the air, especially on the large block between Alameda and Los Angeles where the freeway is abutted by onramps that make overbuild difficult anyway.

Note that while public subsidies might be required to induce air rights development on these parcels, the public contribution would hopefully be less than what would be needed to build the cap park. The air rights development would also be beneficial because it would create tax-paying properties and generate more users for the cap parks. More users close to the parks means more successful parks.

With the block between Main and Spring used for air rights development, it’s logical for the next block to the north to be another cap park, between Spring and Broadway. I’ve updated the crappy MS Paint graphic from my post on the 101 to show this concept. Click to enlarge.

Broadway to Grand

As you can see from the graphic, I didn’t do much to cap the freeway between Broadway and Grand, because the value of doing so is lower in this area. Between Alameda and Broadway, the 101 is spanned by 5 bridges with spacing between 350 and 550 feet. It’s over 1,200 feet from Broadway to Grand, with no side streets. In addition, this area is bounded by the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels and the Cortines School, both of which have logically turned their backs to the freeway.

With no side streets and little prospect of redevelopment on the abutting properties, there will be very few generators of park users for this quarter-mile stretch. Therefore, in this area I think it makes sense to terminate the park with an air rights building between Broadway and Hill. This building could provide a way to bridge the grade difference between Broadway and Hill to help integrate Hill into the street network.

If anything is to be done at Grand, I’d favor an air rights building on both sides of the street, which would reconnect the street façade from Temple to Chavez.

Alameda to LA River

In this area, I disagree with the Park 101 approach. This area is industrial, and there are overhead transportation facilities (the Gold Line and the El Monte Busway). If the Union Station run through tracks and the CAHSR project are constructed, there will be even more overhead transportation facilities. Those facilities are noisy, and the railroad tracks have sharp curves, which makes them noisier. It’s not going to be very pleasant to hang out underneath these bridges, and not many people are going to want to live or work in expensive high-rises adjacent to them.

In this area, Park 101 would also require taking a large amount of property by eminent domain. Progressives seem to have this weird MO where they worry about the loss of industrial and manufacturing jobs in cities in theory, but promote plans that eliminate those jobs in practice (see the Cornfield for example). Now, maybe industry won’t be the best use of this land when Regional Connector is complete and Little Tokyo and the Arts District keep growing, but that can be addressed by upzoning and letting property owners decide what to do. That puts money into city coffers rather than draining them.

For now, this area is a functioning industrial zone, so I think we should let it be. I put in one air rights development on the east side of Alameda to help reconnect the street façade with Union Station.

Main to Spring Option

As another option, I would consider making the block between Main and Spring a park instead of air rights development. This would create a three-block long park between Aliso and Arcadia from Los Angeles to Broadway. With development on Aliso and Arcadia, and air rights development to terminate the view at Broadway and Los Angeles, this would work pretty well too. It would cost a little more in terms of structure and ventilation. Click to enlarge.

Freeway Widening

The Park 101 Study assumes that the 101 would be widened by at least one lane. The conceptual section on page 45 appears to show a clear span of about 100’ on the 101 north and about 85’ on the 101 south. In contrast, most of what I’ve shown assumes a clear span of about 65’-80’. This is a big difference, because the costs do not scale linearly. Long spans require deeper structures and are considerably more costly; this is the reason that air rights have negative relative value.

District 7 may not want to hear it, but the 101 is wide enough here. Much of the congestion northbound is spilling back from the merge at the Four-Level, which means unless they’re planning to build a fifth lane all the way to the Hollywood Split, widening here won’t do too much. Southbound, the congestion builds back from the East LA Interchange and is related to merging, weaving, and capacity issues on the 60 east and the 5 south. Again, those issues are not going away anytime soon. Personally, I wouldn’t feel too bad about locking the 101 into its current number of through lanes here, and this isn’t even an anti-freeway blog.

Summary

Both of these options create considerably less open space than Park 101, but I think the open space created would be more valuable. These options would also allow more development, which generates more revenue for the city. I don’t think the area is at a loss for open space; Grand Park is close and the Cornfield and Elysian Park aren’t too far to the north. I think these options would be more affordable, which means they could be implemented sooner and would have less of an impact on our ability to improve parks elsewhere in the city.

No one should interpret this as an attack on the Park 101 concept; I’m sure a lot of work has gone into the project. The point here is to realize that there are many options beyond just capping the freeway with parks, and we should look at a wide range of alternatives and realize the trade-offs between them.

From 2nd to Union

That about wraps it up for my look at this area for the time being. If I could emphasize one point above all else, it would be the thing that makes a park great is the city around it. Planning in this area needs to start with that fact as the central premise.