The Census Bureau has released its 2014 estimates for population and housing units at the county level, and the data confirms that Los Angeles, and California in general, are not experiencing a housing boom. In fact, housing construction is still not keeping pace with population growth. We’re still digging the hole, and the deficit of housing units is growing larger.

A simplified way of looking at this is to compare the increase in population to the increase in housing units. If fewer housing units are constructed than should be expected from population growth, our housing situation is getting worse, and unfortunately, that’s what’s happening:

This table shows population growth and housing growth for 2010 to 2014. In that time period Los Angeles County built 37,437 housing units, but population grew by 298,041, so in effect, we only built 1 housing unit for every 8 new residents. If the ratio of population growth to housing growth (pop/DU) is larger than the average household size, the housing crunch will get worse. Since pop/DU was 8.0 and average household size was 2.85, LA County’s housing crunch worsened.

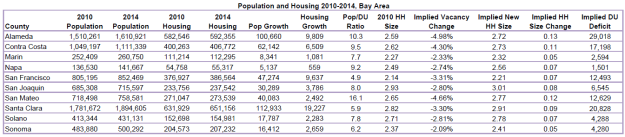

This trend holds for the Bay Area as well.

Note that as some observers have suggested, the relative pop/DU ratios for the Bay Area seem to indicate that, while not building enough, San Francisco is doing better than some other nearby counties. (Hi, San Mateo!)

Some commentators, including Aaron M Renn and Chris B Bradford, have questioned the accuracy of the census data on population and housing estimates in recent years, given how large errors in previous estimates. While I don’t know if the census methodology is good or not, we can look at a few metrics to see if the population and housing changes are at least internally reconcilable:

- Implied Vacancy Change: this is how much dwelling unit vacancy would have to drop to keep household size constant, given housing and population growth. The implied vacancy change for LA County is -1.95%, consistent with what USC’s Casden Multifamily Report says happened between 2010 and 2014. Implied vacancy changes in Orange County and the Inland Empire are also within reason compared to that data.

- Implied New Household Size: this is how much household size would have to increase to keep vacancy constant, given housing and population growth. Because the existing housing stock is large relative to housing stock growth, the increases are relatively small, so accommodating population growth by increasing household size is also plausible.

- Implied DU Deficit: this is how much more housing would need to be built to keep both vacancy and household size constant, given housing and population growth. These numbers are within reason relative to the annual housing deficits that the LAO reported in its study on housing affordability, for coastal counties. Inland counties have an implied deficit by this methodology, but they do not per the LAO. This is a sort of sketchy metric because lots of counties, especially inland counties, were still working through the hangover from the housing crash in 2010.

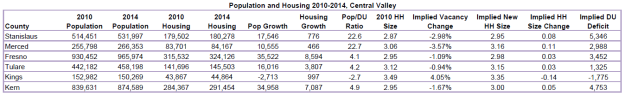

We can also look at a part of California that does not have affordability problems: the Central Valley.

Counties are listed from north to south. Counties on the fringe of the Bay Area (Stanislaus and Merced) had very high pop/DU ratios, perhaps because they were working through inventory from the crash. Fresno, Tulare (Visalia), Kings, and Kern (Bakersfield) Counties all had pop/DU ratios below 5.0, consistent with faster housing growth keeping prices down.

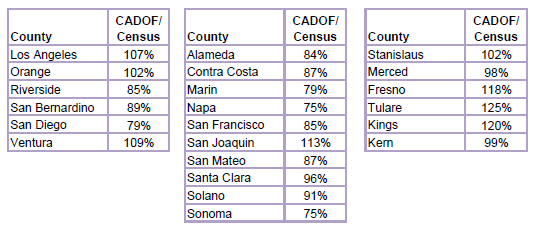

Lastly, I compared the Census estimates with the California Department of Finance’s estimates, which ranged from 75% to 125% of the Census Bureau’s value, including very close values for Los Angeles and Orange Counties.

This doesn’t confirm the census data is right, but it certainly shows that a combination of dropping vacancies and increasing household size could easily accommodate the indicated trends in population and housing stock growth.

California’s housing crisis is continuing, and won’t abate until we start making a serious dent in our shortage of housing supply.